Canine primary hypothyroidism is both an under-diagnosed and an over-diagnosed condition, with an estimated overall prevalence of 0.2 percent in the population (Panciera, 1994). Under-diagnosis is likely as a result of vague and often mild clinical signs, while over-diagnosis is due mainly to inappropriate timing of the testing and the sometimes challenging nature of the interpretation of results. Multiple parameters are available for the assessment of thyroid status in dogs, and the focus of this article will be on selection, timing and interpretation of these tests.

Timing

The most crucial decision when considering thyroid testing in dogs is the appropriate time to perform the testing. The inherent challenges associated with interpretation of endocrine testing mean that if the timing of testing is not appropriate, the correct interpretation of the results may be impossible.

Consideration of testing timing begins with patient selection based firstly on signalment and clinical signs

Consideration of testing timing begins with patient selection based firstly on signalment and clinical signs. The majority of patients with clinical primary hypothyroidism will be middle-aged to older dogs (four to six years old or above), but patients can begin to develop early subclinical thyroiditis from the age of two years (Graham et al., 2007). This difference between onset and clinical signs reflects the length of time it takes for chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis to destroy the majority of the functional tissue. The most common clinical signs seen in clinically hypothyroid patients are dermatological (particularly endocrine alopecia affecting the flanks, tail and areas of friction) and obesity and lethargy, although a wide range of significantly less commonly seen side effects are also reported (Panciera, 2001; Table 1). However, an important consideration is that hypothyroidism almost never leads to dogs becoming markedly systemically unwell, and therefore patients presenting with pyrexia, vomiting, significant diarrhoea and/or PUPD are not candidates for evaluation for hypothyroidism.

The most common clinical signs seen in clinically hypothyroid patients are dermatological (particularly endocrine alopecia affecting the flanks, tail and areas of friction) and obesity and lethargy

| Clinical sign | Incidence |

|---|---|

| Dermatological | 88% |

| Obesity | 49% |

| Lethargy | 48% |

| Weakness | 12% |

| Bradycardia | 10% |

| Neurological signs (various) | Less than 4% for individual clinical signs |

Even when there is ongoing or historic suspicion of hypothyroidism, it remains important that unwell dogs are not tested for hypothyroidism. This is because many of the thyroid parameters we can measure are suppressed by non-thyroidal illness syndrome (NTIS). In dogs, it appears that T4 is the most commonly suppressed parameter, but T3, free T4 (fT4) and TSH are all reported to be suppressed in a lesser proportion of patients (Mooney et al., 2008; Scott-Moncrieff, 2015).

The absence of blood changes does not necessarily completely exclude hypothyroidism. More important than the presence of typical abnormalities is the absence of other significant change

Another important means of screening for potential hypothyroidism cases is blood testing, particularly biochemistry and haematology. A number of parameters are classically altered in hypothyroidism (Table 2); however, the absence of blood changes does not necessarily completely exclude hypothyroidism. More important than the presence of typical abnormalities is the absence of other significant changes. For example, moderate to marked increases in liver parameters or the presence of marked hyperglycaemia or moderate to marked azotaemia are not consistent with primary hypothyroidism and are indicative of non-thyroidal illness syndrome. Nor is the presence of a significant inflammatory leukogram consistent with hypothyroidism. Like with inappropriate clinical signs, the presence of these findings renders interpretation of thyroid testing very challenging and as such, treatment of the non-thyroidal illness should be undertaken prior to any thyroid testing.

| Laboratory abnormality | Incidence |

|---|---|

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 75% (Scott-Moncrieff, 2015) |

| Non-regenerative anaemia | 30% (Panciera, 2001) |

| Mild increases in liver/muscle enzymes | Unknown – due to hypothyroid myopathy (Scott-Moncrieff, 2015) |

| Hypercalcaemia | Less than 2% – one report only (Lobetti, 2011) |

Interpretation of testing for hypothyroidism

T4 (in the absence of TSH or other markers)

Measurement of T4 alone, without the measurement of TSH, is a poorly sensitive and specific test for hypothyroidism (Thompson, 2022). This is due to the significant overlap between dogs with hypothyroidism, non-thyroidal illness and normal dogs (Scott-Moncrieff, 2015). Theoretically, a normal T4 should be useful for screening for hypothyroidism (ie to rule it out); however, even this is not reliable.

T4 and TSH

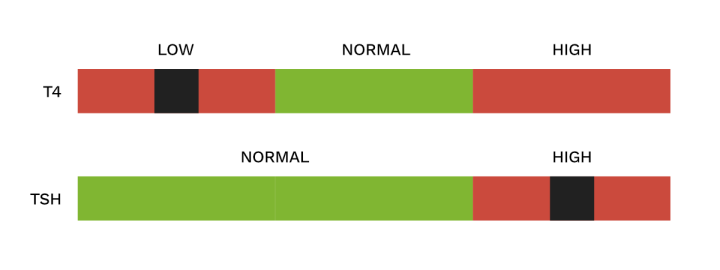

T4 measurement combined with TSH measurement is the most frequently used, and overall probably the most practically useful, means to screen for hypothyroidism. TSH is released by the pituitary gland and works to stimulate the thyroid glands to produce T4. In primary hypothyroidism, where the thyroid gland is atrophied, there will be reduced T4 production and, due to a loss of negative feedback to the pituitary, an increase in TSH (Figure 1).

It should be noted that the normal range for TSH in dogs extends below the assay’s lower limit of detection. As such, detection of “low” levels of TSH is not possible.

In the presence of consistent clinical signs and in the absence of other detectable disease, these results are highly predictive of primary hypothyroidism. This would be considered enough evidence to make the diagnosis and begin the patient on treatment.

However, not all combinations of T4 and TSH are as simple to interpret, with two other patterns of results returned regularly (Figures 2 and 3).

In this case, T4 is suppressed and so measures low, but because there is no actual deficiency in T4 production, there is no loss of negative feedback to the pituitary

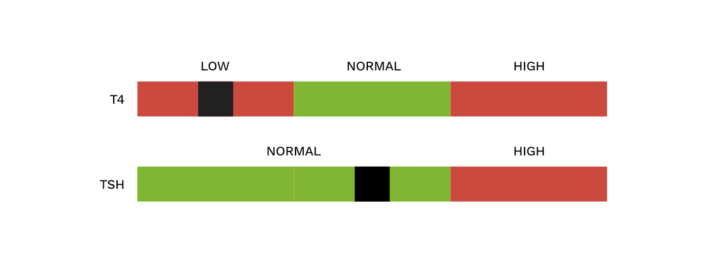

Some tests will detect low levels of T4, but accompanied with normal levels of TSH (Figure 2). The most common cause of these results is non-thyroidal illness. In this case, T4 is suppressed and so measures low, but because there is no actual deficiency in T4 production, there is no loss of negative feedback to the pituitary. This causes TSH to remain in the normal range. The overall likelihood is that this patient is not hypothyroid and has another, non-thyroidal, illness that has caused the T4 suppression. However, this is not guaranteed.

Particularly in cases where the TSH is near to the upper reference interval, it is possible that the patient has both a non-thyroidal illness andhypothyroidism. This is because non-thyroidal illness can occasionally (but only rarely) lead to suppression of TSH to a sufficient extent to reduce what would have been a high TSH into the normal range. The only appropriate course of action here, in order to be certain, is to identify and treat the non-thyroidal illness and then retest the T4/TSH one to three months later. If the patient remains well and the results unchanged, a final consideration is that this could represent normal variation for that individual patient.

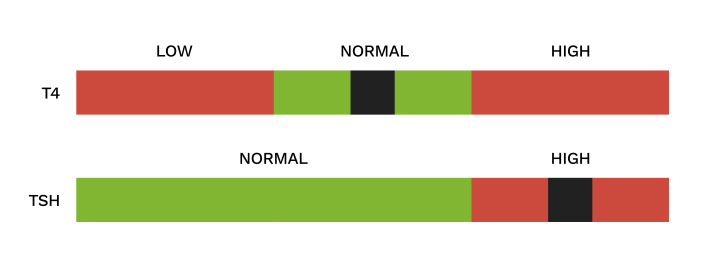

The other commonly seen pattern of changes is that demonstrated in Figure 3.

This is one of the most challenging situations to interpret. When T4 levels are normal but TSH is high, broadly speaking there are likely to be four potential explanations for the result:

- Recovery from a resolving non-thyroidal illness

- Early, subclinical hypothyroidism

- Clinical hypothyroidism with the presence of T4 autoantibodies

- Normal variation

In the case of recovery from non-thyroidal illness, it is hypothesised that there is an increased demand for T4 to resolve the recent suppression. This is reflected by the increased TSH, which is expected to return to the normal range after the non-thyroidal illness has resolved and the T4 levels are once again stably normal. In view of this, the first course of action when receiving a result like this is to take no action at all for one to three months. After this time, the T4/TSH should be rechecked (assuming the patient remains well) to establish whether the TSH has normalised, and to screen for reduction in T4 that might indicate progressive hypothyroidism.

In the case of recovery from non-thyroidal illness, it is hypothesised that there is an increased demand for T4 to resolve the recent suppression

If, after the T4/TSH is repeated, the TSH remains elevated and the T4 remains normal, consideration must turn to the possibility that the patient has early hypothyroidism. In the early stages of the disease, when lymphocytic thyroiditis has begun but there remains sufficient thyroid tissue to maintain a normal thyroid level, an increased TSH concentration will be required to stimulate a smaller volume of thyroid tissue to produce the same overall amount of T4. This results in normal T4 but an apparently raised TSH. Early hypothyroidism is, by definition, asymptomatic, as adequate T4 levels remain in circulation; however, it is likely that clinical signs will develop months or years in the future. These patients do not require thyroid supplementation until the T4 becomes measurably low, and so the appropriate course of action is to remeasure T4/TSH every 4 to 12 months to monitor for the development of overt disease.

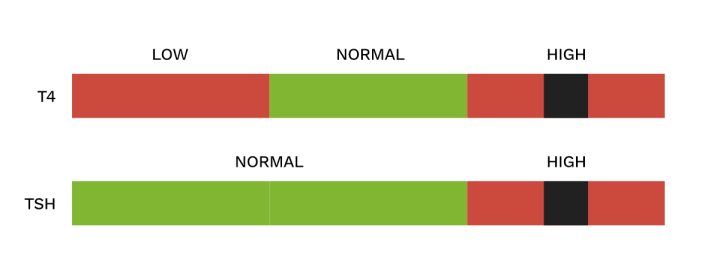

In some cases, patients can display signs very consistent with hypothyroidism, but present with what appears to be early hypothyroidism with normal T4 but elevated TSH ... or even with high levels of both T4 and TSH

In some cases, patients can display signs very consistent with hypothyroidism, but present with what appears to be early hypothyroidism with normal T4 but elevated TSH (as in Figure 3) or even with high levels of both T4 and TSH (Figure 4). In these circumstances, the remaining possibility is that these patients are indeed overtly hypothyroid, but that there are factors interfering with the T4 assay that lead it to read artificially high. These factors are T4 autoantibodies: circulating antibodies against T4. Because the commonly used total T4 assays are antibody-mediated binding assays, the presence of these T4 autoantibodies leads to a false increase in the measured total T4 (Thompson, 2022).

There are two ways to attempt to establish whether this is the case. The first is to try to measure T4 autoantibodies. This test is available from commercial laboratories, and if the test is positive, it implies that there is some degree of inflation of the measured T4 levels. Unfortunately, however, this does not indicate to what degree the number is inflated, and so in the case of results similar to Figure 3 or Figure 4, it will not differentiate overt hypothyroidism from early hypothyroidism. Equally, the test is not 100 percent sensitive, so a negative result does not exclude the presence of T4 autoantibodies.

Equilibrium dialysis is not affected by T4 autoantibodies, and therefore if free T4 returns robustly low in a patient with compatible clinical signs and an increased TSH, overt hypothyroidism can be confirmed and treatment undertaken

The second means of assessing for the possibility of antibody interference is by measurement of free T4 by equilibrium dialysis. It is important to ensure that the laboratory you are using for free T4 uses an equilibrium dialysis assay, as free T4 can be measured in multiple ways (including antibody-mediated immunoassays which can also be affected by T4 autoantibodies). Equilibrium dialysis is not affected by T4 autoantibodies, and therefore if free T4 returns robustly low in a patient with compatible clinical signs and an increased TSH, overt hypothyroidism can be confirmed and treatment undertaken.

Other available tests: T3 and thyroglobulin autoantibodies

The other available tests are T3 measurement and thyroglobulin autoantibodies (TgAA). T3 is of very minimal value above and beyond the tests already discussed, and is therefore not routinely recommended as part of investigations. T3 is produced in circulation directly from T4, and therefore reflects measurable T4 levels. There is also a high prevalence of T3 autoantibodies, which interfere with measurement and interpretation (Graham et al., 2007).

The other available tests are T3 measurement and thyroglobulin autoantibodies (TgAA)

Thyroglobulin autoantibodies are detectable in around 50 percent of hypothyroid dogs (Graham et al., 2007). These indicate an autoimmune response directed at the thyroid gland, and so are suggestive of the presence of lymphocytic thyroiditis in the suspected clinically affected patient. Unfortunately, the presence or absence of TgAA does not give any indication of the degree of progression of thyroiditis, and therefore is of no assistance in differentiating between early subclinical hypothyroidism and overt hypothyroidism. As such, this test is of very limited value above and beyond the combination of T4/TSH, and therefore is not routinely recommended for the diagnosis of clinical hypothyroidism. Negative TgAA are also not adequate to exclude hypothyroidism (as 50 percent are negative), nor does the presence of TgAA guarantee that subclinical or overt hypothyroidism will ever develop.

Negative TgAA are also not adequate to exclude hypothyroidism (as 50 percent are negative), nor does the presence of TgAA guarantee that subclinical or overt hypothyroidism will ever develop

FIGURE (5) Flowchart for T4/TSH interpretation

FIGURE (5) Flowchart for T4/TSH interpretation

Summary In patients with appropriate history, clinical signs and haematological/biochemical changes, and in the absence of evidence of other non-thyroidal illness, a combination of T4 and TSH is the most practical means of assessing for hypothyroidism (Figure 5). In some cases, interpretation is straightforward, but in others there are multiple potential explanations for a given set of results. The addition of free T4 and T4 autoantibodies can assist with understanding; however, often repeat testing after a number of months is the most appropriate course of action.