Prolapse of the nictitating gland or “cherry eye” is the most prevalent third eyelid condition affecting dogs. Patients present with a bulging mass, which may be subtle or obvious, at the lower eyelid and medial canthus (Figure 1).

Together with the undesirable aesthetic appearance, a “cherry eye” can result in significant secondary ocular pathology.

Anatomy and pathophysiology

The nictitating gland consists of seromucoid tubuloacinar glandular tissue that is loosely supported by a T-shaped hyaline cartilage and maintained in place by muscular fasciae and periorbital smooth muscle fibres. Studies have shown the gland to be responsible for approximately 30 to 50 percent of the aqueous portion of the tear film (Helper et al., 1974; Kaswan and Martin, 1985). The gland also plays an important role in ocular immunology (Schelgel et al., 2003; Premont et al., 2012).

| Giant breeds | Great Dane, Newfoundland, Neapolitan Mastiff |

| Large breeds | English Bulldog, Cane Corso, Poodle |

| Small to medium breeds | Pekinese, Basset Hound, American and English Cocker Spaniels, Shih Tzu, French Bulldog, Beagle, West Highland White Terrier, Shar Pei, Yorkshire Terrier, Cavalier King Charles Spaniel |

The exact pathological processes that result in a “cherry eye” are unknown, but it is proposed that a combination of factors may be involved. These include connective tissue band laxity, allergic inflammation and lymphoid hyperplasia in young animals (Mazzucchelli et al., 2012; Multari et al., 2016; Peruccio, 2018).

Since the condition appears to affect certain breeds more frequently (Table 1), it is likely that there is a hereditary component to some factors. Indeed, gland prolapse has been found to have a significant breed predisposition (Gomez, 2012; Mazzucchelli et al., 2012; Multari et al., 2016). Several authors have observed that brachycephalic breeds appear to be more at risk, possibly related to their more generalised abnormal orbital conformation (Mazzucchelli et al., 2012; Multari et al., 2016).

Incidence

In a retrospective study by Mazzucchelli et al. (2012), “cherry eye” in dogs was shown to be a disorder of young animals with 75.4 percent of cases occurring between two and seven months of age. The risk of prolapse appeared to decrease dramatically after dogs were over three years old.

In the same study, 64 percent of patients initially presented with unilateral gland prolapse. However, after three months, over two thirds (71 percent) of these unilateral cases developed prolapse in the contralateral eye. In total, this means that 45 percent of patients will suffer from bilateral disease.

Consequences of the disorder

Keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS or “dry eye”) is the main risk associated with the disorder that is discussed in published literature. Morgan et al. first reported the problem in 1993, where it was found that 42.8 percent of untreated “cherry eyes” developed KCS.

Historically, the treatment for “cherry eye” was excision of the gland, but several studies drew correlations between gland removal and the development of KCS (Helper et al., 1974; Dugan et al., 1992; Morgan et al., 1993). This is especially relevant in current times given the popularity of brachycephalic breeds who also display lacrimal hyposecretion and a poor aqueous tear reserve (Saito et al., 2004; White and Brennan, 2018).

Treatment

Replacement procedures are the current gold standard for treating prolapsed glands. These encompass “pocketing” and “anchoring” surgical techniques, which are employed both individually and combined, along with several described modifications (see below for details).

The decision to pocket or anchor a gland often comes down to a surgeon’s preferences and experience. Combined anchoring and pocketing techniques have been demonstrated to have value in complicated cases, such as in giant breeds with difficult adnexal conformations or cases with concurrent scrolling of the third eyelid cartilage (Premont et al., 2012; Multari et al., 2016; Michel et al., 2019).

If there is significant inflammation affecting the gland, and in the absence of corneal ulceration, preoperative topical anti-inflammatory medications may be appropriate.

Pocketing

Pocketing techniques bury the gland after creating a “pocket” in the subconjunctiva ventral to the globe, with success rates of approximately 90 percent (Premont et al., 2012; Gould and McLellan, 2014; Multari et al., 2016). Magnification, such as using a set of loupes, is recommended to perform the pocketing procedure.

Modified Morgan’s pocket technique – methodology

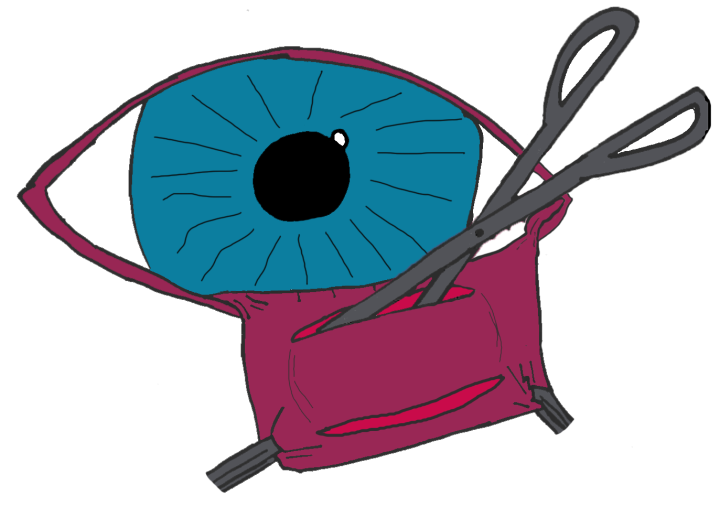

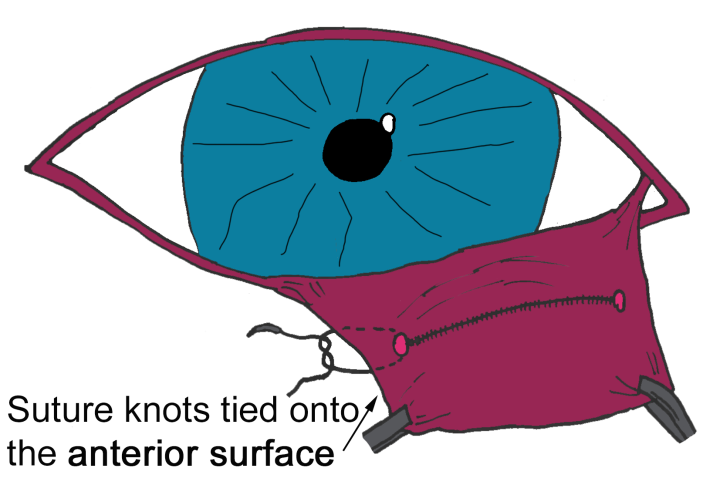

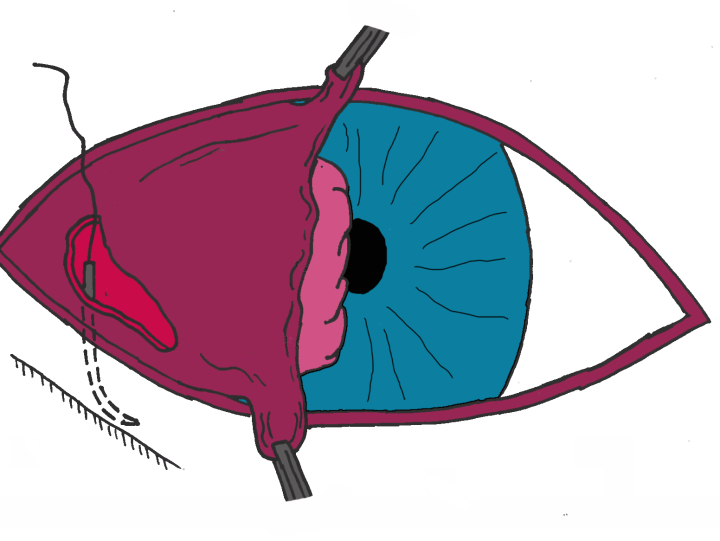

- Step 1: Two curvilinear incisions are made on the posterior surface of the third eyelid either side of the prolapsed gland, creating an incomplete ellipse through the very thin conjunctiva and the fascia immediately beneath the conjunctiva (Figure 2A)

- Step 2: Via blunt dissection, a subconjunctival “pocket” is created inferior and medial to the globe (Figure 2A)

- Step 3: The incisions are partially closed to “pocket” the gland. This is achieved with the placement of absorbable sutures (polyglactin 910 or PDS), leaving a gap at each end of the incisions with knots positioned on the anterior aspect of the third eyelid (Figure 2B)

Anchoring

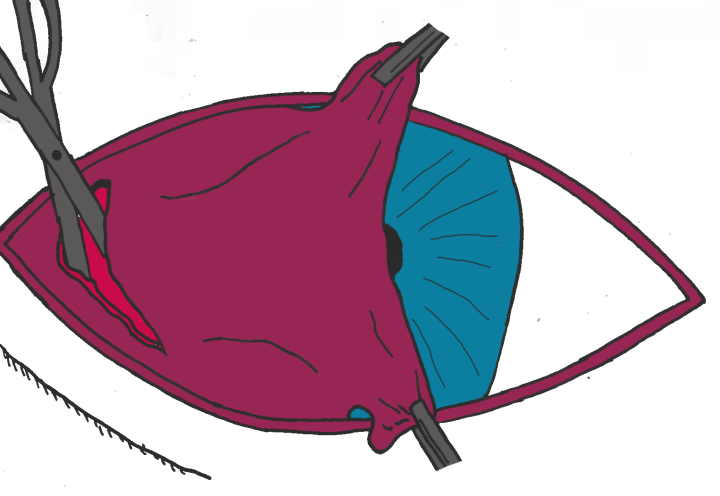

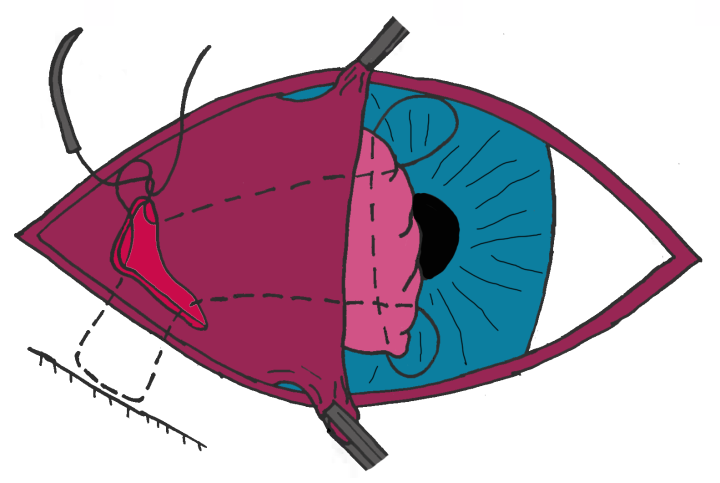

Anchoring techniques involve suturing the gland to the orbital rim, the extraocular muscle(s) or the sclera. The authors’ favoured technique involves suturing the prolapsed gland to the ventral orbital rim (Figure 3; Gould and McLellan, 2014).

Methodology

- Step 1: A small incision is made into the ventral conjunctiva between the third eyelid and lower eyelid allowing access to the orbital rim via blunt dissection (Figure 3A). In some dogs with very tight lower eyelids where this surgical approach would be difficult, the incision can be made through the lower eyelid, directly onto the orbital rim

- Step 2: Using polydioxanone or nylon, the suture needle is passed close to the orbital rim to pick up the periosteum. The needle is then brought back through the initial incision (Figure 3B)

- Step 3: The third eyelid is everted and the needle is passed up through the length of the third eyelid via the initial incision and out through one end of the prolapsed gland. The needle is then turned through 90 degrees and passed along the long axis of the gland to emerge at the other end of the gland (Figure 3C)

- Step 4: The suture is then directed down through the third eyelid and out of the original incision where the suture ends are tied and the gland is anchored to the periosteum of the orbital rim (Figure 3C)

- Step 5: Polyglactin or PDS may be used to close the conjunctival incision but it can be left to heal

Post-operative care

Owners should be warned about third eyelid swelling which is common and can occasionally look like the procedure was unsuccessful or partially successful for the first few days.

An Elizabethan collar and rest are both essential to allow the tissue to heal properly and prevent self-trauma. Post-operative systemic anti-inflammatory treatment such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are recommended.

Complications

Probably the most frequent complication is recurrence of gland prolapse, which even in experienced hands may occur in up to 10 percent of cases (Premont et al., 2012). Traditional anchoring techniques were associated with considerable recurrence rates and a high risk of globe penetration (Kaswan and Martin, 1985; Stanley and Kaswan, 1994; Gomez, 2012).

Less commonly, cyst formation can occur within the third eyelid. This most likely occurs due to complete closure of the incision, leaving nowhere for the secretions of the gland to exit.

Corneal ulcers can form if sutures are left in contact with the cornea; in mild cases a bandage contact lens for a few days can prevent further trauma. In more serious cases the suture material may need to be removed.

Conclusion

“Cherry eye” is a common condition in veterinary practice. Due to the significant disruption to normal ocular health, it is important to treat early to avoid long-term damage and complications.

Surgical replacement of the glands is the best option; pocketing, anchoring or a combination of the two is down to the surgeon’s preference and experience.

Good client communication is key to ensuring owners understand the post-operative care considerations and complications associated with the surgeries before proceeding.