Emergency triage is an essential skill that veterinary nurses must master. In the veterinary practice, the ability to effectively triage a range of cases is crucial to ensure that patients receive timely care. Emergency triage involves rapidly assessing and prioritising patients based on their condition and urgency of need. This process not only aids in managing the workflow in a busy veterinary practice, but also plays a role in improving patient outcomes.

Understanding triage in veterinary medicine

Triage, a term derived from the French word trier meaning “to sort”, is the process of prioritising patients based on the severity of their condition. Emergency triage is the systematic process of sorting patients to determine the priority of treatment based on the urgency of their condition. An effective triaging process will categorise patients by identifying those who need immediate intervention and those whose condition can safely wait. Triage facilitates the assessment of patients according to the severity of their illness to ensure that those requiring immediate attention receive it prior to others (Devey and Crowe, 2007). The concept was developed by Dominique Jean Larrey, a French surgeon in Napoleon’s army, who implemented a system to prioritise wounded soldiers based on the severity of their injuries during the Napoleonic War in the early 19th century. Although mass casualties are unlikely in veterinary practices, there will be frequent simultaneous encounters of multiple patients with varying levels of illness and injury.

An effective triaging process will categorise patients by identifying those who need immediate intervention and those whose condition can safely wait

The primary goal of triage is to identify life-threatening conditions promptly to ensure that patients receive the necessary interventions without delay. This process usually occurs through an initial phone call from the caregiver, but it can be used in the waiting room and in hospitalised patients (Covey, 2018). Newfield (2018) suggests using a telephone triage system so all team members can follow a systematic approach. Using a checklist when answering calls ensures that all relevant information is collected from and given to the client.

The role of veterinary nurses in triage

Veterinary nurses play a pivotal role in the triage process. Their responsibilities include:

- Conducting triage assessments: veterinary nurses are often the first to evaluate the patient, making their role in the initial assessment critical

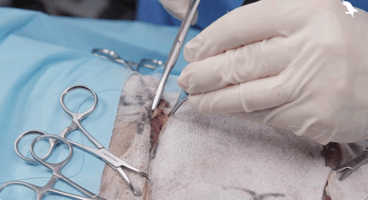

- Administering first aid: based on the triage assessment, veterinary nurses may administer first aid or emergency treatments under the direction of the veterinary surgeon. Under Schedule 3 of the Veterinary Surgeons Act (1966), anyone can administer emergency first aid to save life or relieve pain or suffering (RCVS, 2023). This provision allows for immediate action in a serious situation, even if a veterinary surgeon is unavailable

- Working inter-professionally: in emergency triage, veterinary nurses and surgeons must communicate swiftly and effectively to ensure the best outcomes for patients. Veterinary nurses conducting initial assessments must relay information using concise and clear language so the veterinary surgeon can make quick and informed decisions. Veterinary nurses will also assist veterinary surgeons by preparing patients for further diagnostics or surgery and providing ongoing care. A collaborative vet-led team approach should be adopted to relay crucial information about the patient’s status, anticipated needs and changes in their condition

- Communicating with caregivers: veterinary nurses serve as a vital link between the veterinary team and the caregiver, providing updates on the patient’s condition and explaining the triage process

The triage process

The initial assessment is the first step in the triage process and involves a rapid evaluation of the patient’s overall condition. Once the patient arrives at the practice, the triage process begins with a focused survey of the major body systems, which includes the respiratory, circulatory and neurological systems (Norkus, 2018). This primary survey will yield the most valuable information and involves a 60- to 90-second examination of the clinical parameters. Covey (2018) suggests that the evaluation of these parameters will allow the veterinary nurse to identify life-threatening abnormalities and categorise patients as either stable or unstable. A “capsule history” should be obtained from the caregiver at this point to determine the essential information that could alter the early management of the patient. A more detailed history may be taken once the patient is more stable (Brown and Drobatz, 2018).

A 'capsule history' should be obtained from the caregiver at this point to determine the essential information that could alter the early management of the patient

Performing a primary survey in under two minutes may be achieved with the assessment of the six perfusion parameters as this broadly assesses the major body systems and the patient’s perfusion status (Ho-Le, 2024). The major body systems are vital for maintaining tissue perfusion and any significant abnormality in one or more of these systems can compromise a patient resulting in life-threatening consequences. The six perfusion parameters are:

- Mentation and gait

- Heart rate

- Respiration

- Mucous membranes

- Capillary refill time

- Pulse quality

If a life-threatening abnormality is detected by the veterinary nurse during the triage survey, the patient should be immediately referred to a veterinary surgeon.

Secondary survey

Once the primary life-threatening conditions have been addressed in the initial triage process, the secondary survey involves a more detailed examination. This involves a full physical assessment of the patient and obtaining a detailed history from the caregiver. The purpose of the secondary survey is to identify concurrent problems that were not assessed during the primary survey (Poli, 2021a).

Standardised scoring systems

Effective triage may also involve the use of standardised scoring systems to ensure consistency and accuracy in patient assessment. Several triage scoring systems are available which are validated for use in humans, and some of these have been adapted to suit veterinary patients (Covey, 2018). One such system is the veterinary triage list (VTL) (Ruys et al., 2012), adapted from the human Manchester triage scale. The VTL categorises veterinary emergencies into colours and wait times (Table 1). This system helps veterinary nurses prioritise patients systematically and ensures that those in a critical condition receive prompt attention.

| Colour | Urgency | Triage waiting time |

| Red | Immediate | 0 minutes |

| Orange | Very urgent | 15 minutes |

| Yellow | Urgent | 30 to 60 minutes |

| Green | Standard | 120 minutes |

| Blue | Non-urgent | 240 minutes |

Another method used for triage is the ABCDE approach (Poli, 2021b). This approach is split into a primary and secondary assessment for critical patients which aims to first preserve life, manage life-threatening injuries and re-establish tissue perfusion with oxygenated blood.

The ABCDE approach stands for:

- Airway assessment

- Breathing assessment

- Cardiovascular system assessment

- Disability assessment

- External assessment

Ongoing care through hospitalisation

Veterinary nurses must be vigilant and proactive, recognising subtle changes in a patient’s condition that may indicate a need for further intervention

The role of veterinary nurses in emergency triage extends beyond the immediate assessment and stabilisation of patients. They also play a crucial role in monitoring and supporting patients throughout their hospitalisation. This includes administering medications, providing wound care, monitoring vital signs and offering comfort and reassurance to both patients and their owners while under the direction of the veterinary surgeon. Veterinary nurses must be vigilant and proactive, recognising subtle changes in a patient’s condition that may indicate a need for further intervention.

Conclusion

Emergency triage in veterinary nursing requires a combination of rapid assessment, clinical knowledge and effective communication. By following a structured approach to triage, veterinary nurses can ensure that patients receive the appropriate level of care based on their individual needs. Continuous education and training are essential for maintaining proficiency in triage skills, which will ultimately lead to better patient outcomes and more effective emergency care.

References (click to expand)

| Brown, A. J. and Drobatz, K. J. | 2018 | Triage of the emergency patient. In: King, L. G. and Boag, A. (eds) BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Emergency and Critical Care, 3rd ed. BSAVA, Gloucester, pp. 1-7 |

| Covey, E. | 2018 | How to triage. The Veterinary Nurse, 9, 262-268 |

| Devey, J. and Crowe, T. | 2007 | Trauma. In: Battaglia, A. M. (ed.) Small Animal Emergency and Critical Care. Elsevier, Missouri, p. 205 |

| Ho-Le, S. | 2024 | Tackling triage: how to prioritise patients. Vet Times. [Accessed: August 2024] |

| Newfield, A. | 2018 | Triage and initial assessment of the emergency patient. In: Norkus, C. (ed.) Veterinary Technician’s Manual for Small Animal Emergency and Critical Care, 2nd ed. John Wiley and Sons, Hoboken |

| Norkus, C. | 2018 | Veterinary Technician’s Manual for Small Animal Emergency and Critical Care. Wiley, Hoboken, p. 45 |

| Poli, G. | 2021a | Triage part 2: secondary survey. Vet Times. [Accessed: August 2024] |

| Poli, G. | 2021b | Triage part 1: primary survey. Vet Times. [Accessed: August 2024] |

| RCVS | 2023 | Code of professional conduct for veterinary nurses. Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons. [Accessed: August 2024] |

| Ruys, L. J., Gunning, M., Teske, E., Robben, J. and Songrist, N. | 2012 | Evaluation of a veterinary triage list modified from a human five‐point triage system in 485 dogs and cats. Journal of Veterinary Emergency and Critical Care, 22, 303-312 |